HOW I LEARNED TO BE A MORE COMPASSIONATE TEACHER

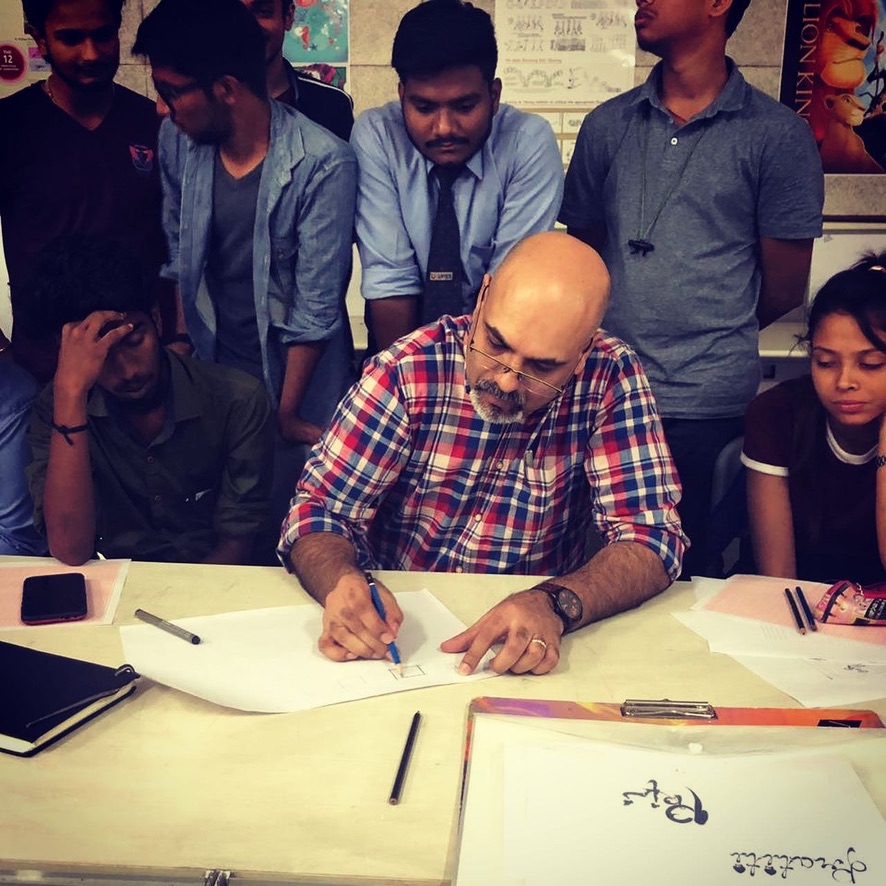

A year or so ago while teaching, I made a big mistake. But also a learned a big lesson in teaching. Yes, even after 14 years of teaching and being an academic administrator, I’m still learning how to be a better teacher.

It was during a session where I was teaching design students some fundamental drawing basics. My mistake was this: I broke a student’s pencil to make a point dramatically. I knew it was a mistake the second after I did it. In fact, I thought it might be wrong even before I did it, but I took a chance and did it anyway and I instantly realised my mistake, the moment I saw the student’s expression. Here I am – former design school Dean, well-respected teacher, trainer of teachers – suddenly faced with the embarrassment of doing the wrong thing in the classroom, with potentially devastating consequences.

But wait… let me go back a bit. You know… for context.

As a relatively experienced teacher who has had good results with students over the years, I’ve sometimes been asked to conduct teacher training at design schools. An important point I try to get across is the need to be a more compassionate teacher. This can sometimes be a hard sell because design teaching (especially the kind you find in architecture schools) has enjoyed a lot of notoriety for being hard on students’ mental well-being. Which is ironic. On the one hand, we teach design students to be empathetic designers – to deeply understand the user, the client, the public… whoever we’re designing for. Design thinking – which is basically empathetic decision making – has become something of a fad, and designers are quick to point out how we have always been empathetic thinkers because we keep the user at the heart of everything we do.

But do design teachers have empathy for design students? In my personal experience… well, let’s just say things could be better. Certainly those days are gone when teachers would tear apart sheets and destroy models, leaving students in shock and in tears. Those habits had already started to vanish by the time I was in architecture school in the mid 1990s. Although my generation of GenX students – the generation infamously known as slackers – would probably have just shrugged such things aside, I think we were starting to foreshadow the coming of the Millennials, who, as we all came to learn, would not stand for such nonsense in the classroom.

But we did get regularly told by some teachers and some jury members that we were lazy, stupid, decrepit, wasting our time, or that we should think twice about continuing in architecture. We regularly had teachers draw marks with permanent marker on our pristine presentation drawings, often to make the not so subtle point that our work was not precious. We were often subjected to sarcasm as a teaching tool, which – unlike current generations – we totally understood as being subtle ways to humiliate us without, you know, actually humiliating us.

When I became a teacher myself, I tried to avoid going down that route (although I do admit that sarcasm has been one of my favourite critiquing tools, now rendered useless by GenZ students who were never raised on steady diet of 1970s British comedy shows like I had been). I never once intentionally sought to humiliate a student or make them feel bad. Unintentionally, though, it’s happened. There are times when I was perhaps a bit overzealous in my disappointment, and to tell the truth, I was never really raised in a household where praise was in big supply. In my house, good work was simply expected, and required no significant lauding beyond the occasional gruff “Ok, good.” Bad work (or worse, bad behaviour) was roundly criticised and punished, and that trend continued through 1990s architecture school. The ability to critique what was wrong in a project or how to improve a project rubbed off on me quite well, but not the ability to impart significant positive reinforcement and make someone feel really happy and motivated about their accomplishments.

But as I mentioned, any shortcomings on my part in teaching were unintentional, and arose more from ignorance and inexperience than anything. I could also blame the mixed signals I used to get from other, more experienced, teachers. Some were always friendly with students, while others said that this was not a good idea. Some said that it’s okay to be “soft”, while others insisted on professional discipline. Often such messages had to do with the divide between academia and industry, and the supposed failure on the part of teachers to enforce rigour and discipline that would result in the inability of graduates to manage with the Real World – the mythical and mystical place where everything was much harder and harsher than the cozy confines of college.

But as I taught over the years, I also learned. For one thing, I learned to dispense with the theatrics I once would employ: slamming the door and leaving the classroom to express my disappointment; or emotionally blackmailing students to make them feel guilty about not doing enough work, while I – busy architect and teacher – was working so hard to teach them. (Ok, I admit I still sometimes do the second one.) And I’ve learned to find a balance between being a student’s friend and also ensuring a sense of rigour and discipline. At least, I’m trying to. Which leads back to the incident where I broke the pencil.

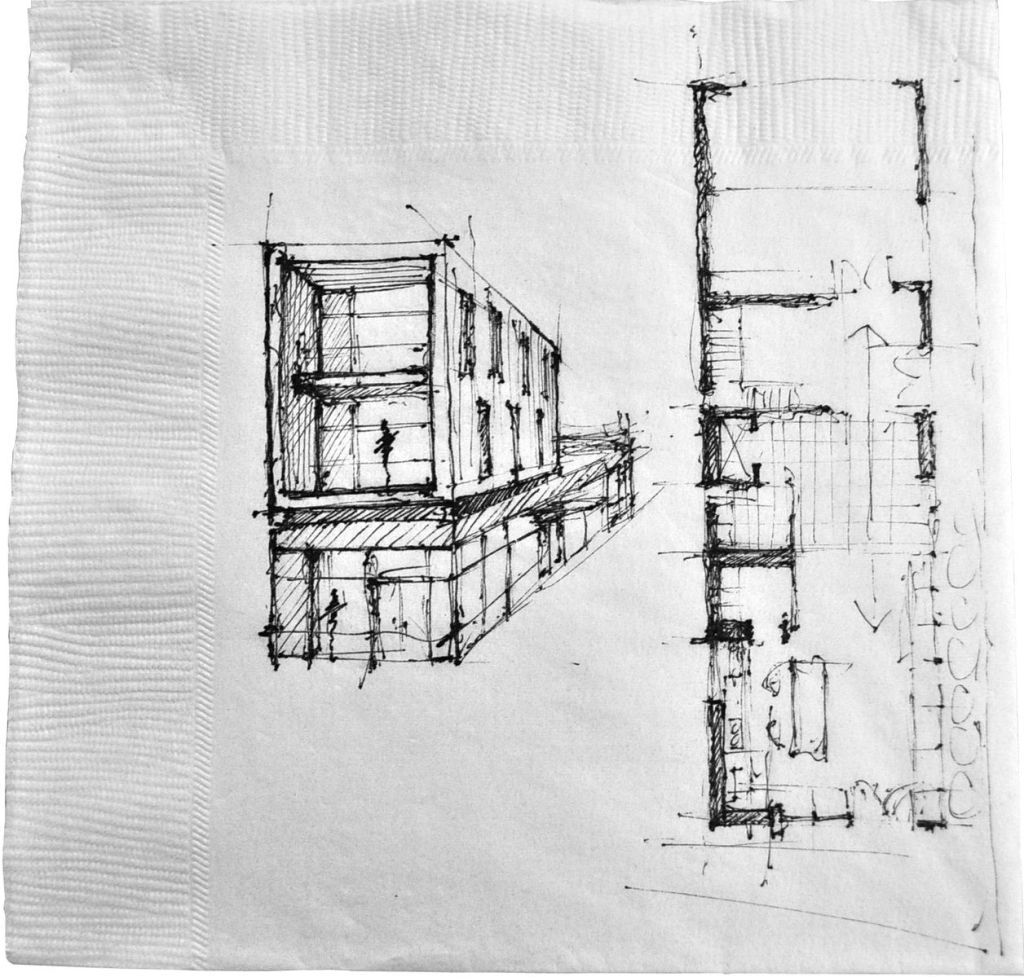

Let me explain the incident in more detail. I was teaching second year design students about manually drawing different orthographic views – top view, side view, etc. I was teaching them how to do this quickly and roughly, but also precisely. Not a super-precise drafted design drawing made with drafting instruments, but drawing a basic plan or elevation accurately by hand – balancing looseness with precision. This is a skill that most designers will need as a professional – the infamous “napkin sketch”, requiring both the roughness of a work in progress and the precision of a drawing that adhered to a correct scale and proportion.

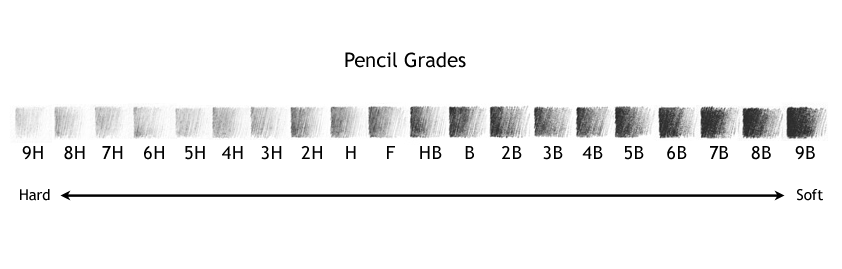

I’d seen some students using hard pencils (or even worse, mechanical pencils) and I was starting to get upset because I would have thought they’d learned how to use soft pencils for rough, loose drawing in their Foundation year. I’d earlier told them not to even bring any pencils harder than HB into the class; we were not going to do any of that kind of precision drawing. I told them to use only soft B-range pencils, meant for rough and loose manual sketching, not for drafting.

In the class I noticed one student – actually one of the more gentler and sweeter students in the class – using an H pencil. I wasn’t infuriated by this, but I did want to make a point right then and there. I don’t know what came over me, but I guess these were students I was teaching for the first time (I visit this university only once a month) and I dipped into my old toolkit of theatrics in order to make some kind of impression on them. I went to the student and – in what I felt was a more amusing than vindictive way – I took her pencil and broke it right in half and pretended to throw it out the open window. Point made. Or so I thought.

The look she then gave me was a mixture of shock, disappointment, and resignation. She took it much worse than I expected. She didn’t say so, but I could see it on her face. I knew instantly that I shouldn’t have done it. I even said something to the effect of “You’re not upset that I broke your pencil, are you? Are you really upset?” I may have even half-heartedly apologised a few minutes later. The student was quick to say how she wasn’t upset, but I could see that she was. For the rest of the class period, this bothered me. I’d miscalculated.

I thought about this for some time, and at the end of the day, I went over to the campus stationery and bought a new pack of soft drawing pencils for her, compelled mostly by guilt, but also because I wanted to make another point, both to myself and to the student. I purchased the pencils and started walking back to where I was staying on campus, and I saw the student outside the design building with a small group of friends. I went up to her and quietly handed her the pack of new pencils and told her that I was sorry, that I was just trying to make a point, and that I realised she was upset.

This was very awkward for her, I thought. In India, there’s still a fairly strong hierarchical divide between teacher and student (we’re still called “Sir” and “Ma’am”) no matter how friendly you try to be. I can’t say for sure, but it could very well have been the first time a teacher had ever genuinely apologised to her, let alone buy her a new pack of pencils. She was effusively trying to tell me how it was ok, and she didn’t feel bad, and how I didn’t have to do this, but I insisted. And despite the awkwardness, I could tell she was touched by the gesture.

And this is where I finally get to my point in all this. This act, this gesture, this episode of disappointment followed by camaraderie – this balance between being a bad guy and being a good guy – this is what I’ve learned is at the heart of teaching. This is the existential nature of what we as teachers do. We make mistakes and we sometimes make students feel bad, and this is forgivable most of the time, but we must – without exception, without delay – follow that up with compassion and goodwill. It’s what makes us human, and we need students to understand that we’re human, otherwise that divide between student and teacher will never be bridged.

That act of breaking her pencil and then immediately buying her a new set, this act helped to convey both the seriousness of what I was teaching and the empathy of understanding that mistakes can happen, that it’s ok, it’s not a bad thing. It also conveyed that I was a real person, not just a figurehead with a bank of knowledge to impart. I haven’t discussed this incident with the student since then, but I genuinely think that we reached an understanding that day, and we smoothed a pathway toward future learning, where she knows that, as a designer, I’m not only very serious about what I do but that I also don’t take it too seriously. And that has led to more effective learning. The student really put in a lot of effort in that workshop that semester, and was one of the most diligent and enthusiastic students in the class. It’s possible that she was this way well before the Broken Pencil Incident, but I like to think that whatever barriers may have stopped her from going the extra mile in that workshop were dismantled by our mutual encounter.

I later taught another workshop at the same university, with the same student in the class. This time we were doing an anthropometrics exercise – mapping the way the human body interacts with furniture. During the mapping process, I wanted the students to use a digital tool which most had never used, as a means to do the tedious mapping more quickly. The ‘pencil student’ at first hesitated to use the digital tool, and insisted on doing the mapping by hand, but I insisted that she try it and get out of her comfort zone. Reluctantly she did it, and soon realised how much easier it was to do it digitally, and mapped her anthropometric diagrams successfully. I like to think that her willingness to change her medium was partly based on the trust we had earlier established. That she tried something new because she knew that if I suggested it, then it was worth doing.

I may never know this for sure (or maybe I will when she reads this), but I do think that rigour and discipline can go hand in hand with compassionate, friendly teaching. I’m often tough with my students, and I often expect a lot from them – a lot of work or a lot of critical thinking. But before I ask them to do so much work for me, I try to build a foundation of trust and compassion, I let them know that I’m a friend, and that I’m here for them in a real and human way. As teachers, we often forget this, and we expect students to work hard simply because they should. Because they’ve engaged in some holy contract by enrolling in a design school for which they should feel pride and nobility. But this is not always enough of a buy-in. This value has to be proven, and the steps to prove it require teachers to engender trust with our students. The trust can’t come after the fact, like it did in our generation of academics. We trusted our teachers after they put us through the ringer, but that doesn’t work anymore. A teacher needs to earn that trust before, and then you can expect the magic to happen.