Yesterday, I finished up some long-pending academic work and as a reward for not procrastinating, I took a break and watched the movie Nomadland. What follows is not so much a review as a long-ish reflection on the film – a reflection on myself as an audience member as well as an architect, because it really made me think a lot about architecture, housing, and the built vs. natural landscape. There are significant spoilers in this article, but since Nomadland is a non-narrative movie, I’m not sure if knowing about spoilers will detract from enjoying this film. But if you haven’t seen it and don’t like spoilers, stop reading now.

——–

As a long-time Frances McDormand fan, I’d been eager to see Nomadland well before it was nominated for any awards, but it only became available for streaming here in India a week ago. It has now, of course, won a caravan full of awards, including the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actress (all three were history-making awards).

I really loved this film; I kind of knew I would, based on everything I’d read about it. But it was affirming to see that it was such a good film after all, even though several friends had expressed their not-so-subtle dislike of it. Most of their criticism is centered on its ‘slogginess’; that it’s a slow, drawn out, meandering character study that doesn’t follow a traditional narrative structure. I’m not even sure that it has a narrative structure at all, let alone a traditional one, and I can see how that might disappoint people for whom story and development are necessary for a film. While I’m a big proponent of narrative in all things creative, I can also appreciate when narrative is purposefully set aside in favour of impressionism, which this movie does very well. In this respect, it’s a credit to Chloé Zhao that the film was also nominated for Best Editing. That’s really where this movie shines in its impressionistic qualities, lingering on a shot when it needs to linger, and moving us through quick shots when it needs to do that. But yes, there’s a lot of lingering, with a slow pace, a minimal soundtrack, and many moments without dialogue. Any good film in which the landscape is essentially a supporting character is bound to have long, slow scenes where characters just gaze into the distance (see the poster above).

THE INTUITIVE NEED FOR DETACHMENT

But why do they gaze? Because this film is ultimately about detachment – from society, from people, from permanence, from the built environment. It depicts the often solitary life of American ‘nomads’, people who voluntarily choose to live a ‘houseless’ life, wandering from place to place, job to job, across the natural and incredibly beautiful landscapes of the American continent. The reasons why they do so vary, and for Fern (the main character played by McDormand) it’s mostly triggered by the dual events of her husband’s death from cancer and the complete shutdown of her livelihood – a gypsum company in Nevada that closes not just the mine and plant, but the entire town as well. The company owned all the houses, so she buys a van, customizes it herself, puts her few possessions into storage, and casts herself adrift into the deserts, mountains, plains, and coasts of the vast unpopulated lands of the American West.

Many of these landscapes are deeply familiar to me. In 2013, after finishing my masters degree, I took a solo 6-week road trip across the United States and drove through many of the places depicted in the film – the Badlands of South Dakota, the deserts of Nevada, the California coastal highways along the Pacific Ocean. I felt drawn to the same sense of detachment one feels in the presence of such awesome natural panoramas. I felt a hint of the same fragmented kinship one feels with the random humans one encounters while driving through the emptiness. I’ve spent most of my life living in cities and most of my career designing buildings in dense urban areas, places for intense and lively social interactions. I’ve designed housing for upwardly mobile, career-oriented professionals; housing that is almost never occupied by the same person for more than a few years and is often considered more of an investment than an actual permanent home.

The road trip – and now this film as well – made me reflect on the role of architecture in this environment, and how much of what is built is designed around attachment to possessions, and also to other people. The former is often criticized, but the latter is generally found to be a universal good. Making spaces for people to interact and know each other is considered aspirational for all.

But it discounts the often conflicting urge towards detachment. I almost titled this article The Architecture of Loneliness before I realized that it’s not about being lonely (although that may be a component). Loneliness implies negativity, sadness – a desire to connect but an inability to do so. Rather, I think it’s about detachment, which doesn’t necessarily carry those negative connotations. Detachment is purposeful and intentioned. I’ve come to realise that all human beings, even the most extroverted, do have an instinctive need for detachment, however miniscule. The nomads depicted in this film have simply accepted and acknowledged this part of themselves, and indeed it’s often triggered by some life event, or some loss or desperation.

I think the movie expresses this beautifully. Fern has family (a sister is depicted) but chooses to detach from them. She does have friends, and is generally a friendly and easy-going person, but she only sees them in short stretches, when their meandering paths happen to cross or overlap. She has an attachment to some things, even – the dishes bought by her father over years of garage sales, her husband’s Carhartt jacket which she constantly wears, and of course her van itself. But she resists the markers of more permanent attachments. She doesn’t stay long in any one job and doesn’t have a career to speak of. She resists the trappings of traditional permanent family life. This is made explicitly clear in a scene in which she visits a friend in California – Dave, a former nomad who chose to re-attach himself to his son’s life after the birth of his grandson. They live in a beautiful and comfortable farmhouse and even though it’s not your typical dense suburban community (there are no visible neighbours anywhere), Fern still finds herself reflecting on how much of a permanent HOME it represents. Dave invites her to stay there with him indefinitely, but she resists, and leaves early in the morning without warning, lest she become tempted by the lifestyle of domestic permanence. She resists forming those attachments again because she knows what it means to lose them. She again casts herself adrift.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF NOMADIC LIFE AT MICRO SCALE

What struck me about the film was how much it made me think about architecture at different scales. In particular, I was deeply interested in seeing the interiors of the various vehicles that nomads use as their roving homes. The small details of how the interiors are designed for minimal space. Fern is proud of how she’s built her van to suit her minimal needs – sleeping, cooking, and even using the toilet in the tiny space. One of my favourite scenes is when Fern and her two nomad friends check out a display of giant luxury RVs that are stocked with washer/dryer, bathrooms, TV – the works. Many of us have seen such things, especially since there seems to be a sudden boom in #vanlife hashtags in the last few years. A few American travel vloggers that I follow on YouTube have adapted to the global pandemic by shifting to RV travel within the US only. As a designer, I’m as interested in how they build and use the interiors of their vans to suit their needs. I’m interested to see how they design and customise their space with clever details and gadgets, and how they prioritise certain luxuries over others.

Clearly, the scene with the luxury RVs is meant to contrast with the simple lifestyles of the movie’s nomad characters. None of them would ever actually buy a luxury RV, mostly because they couldn’t afford it but also because it represents the lifestyle that they purposely stopped pursuing. Much of what draws them to the nomad life is the raw connection with the landscape around them, which the luxury RVs tend to obscure. Ostensibly, such vehicles are meant to roam the countryside, but the similarity of a massive RV to the conveniences and comfort of one’s actual permanent home can get in the way of fully experiencing the ruggedness of the natural environment. (“Glamping” is a thing, in case you’ve never heard of it.)

Nevertheless, it’s interesting to see how much of a role that caravan architecture – both the simple and luxurious varieties – plays in this setting, at the personal scale of the single inhabitant. Drawers, panels, and other such details are referred to thoroughly in the film, highlighting the kind of architecture you have to work with when you detach yourself from a permanent, spacious, primary dwelling. Rather than take up a product readymade in a factory, most of the vehicles used by the nomads are personal and informal conversions, made from scraps and waste materials. Toilets are simply buckets of different sizes, and privacy is signaled through the use of coded signage.

Privacy is a key element in the nomad life. When the physical barriers between you and the world around you are broken down, how do you maintain a level of solitude when there are others like you a few meters away? In a scene from the film, when only Fern and her friend Swankie are left in a makeshift RV park after a gathering, Fern knocks on Swankie’s van door for help with a flat tire. But Swankie has signaled her desire for privacy by putting up a Jolly Roger flag and is initially upset that Fern has disturbed her solitude. But naturally, she helps Fern anyway. There’s an underlying Nomadic Code at work here. The nomads are not hermits. They seek companionship and enjoy the company of each other and even that of strangers. They tend to have customer service jobs in tourist areas, and the film doesn’t show them as being antisocial in that way. But like all detached beings, they need their time alone. They are truly introverts who like company and relationships, but in controlled measures, at a distance from each other. They are social but territorial, and the scope of territoriality mirrors that of traditional housing communities but at a much smaller scale. Fern doesn’t like others meddling in her van space and is very upset when Dave tries to help with things but ends up breaking her beloved dishes.

In many ways, the privacy at this scale is condensed and intensified. The nomad’s space is just enough for themselves and a few possessions. Everything is stored in its place and there is a culture of continually giving things away. They are in a lifelong process of shedding parts of themselves which were accumulated in their prior settled existence. At the end of the film, Fern disposes everything that’s left in her storage locker, making a final and definite commitment to detach herself from the legacy of her husband and her previously settled life. The storage locker was essentially another ‘room’ in Fern’s metaphysical ‘house’ and by removing it, the architectural scale of her ‘home’ becomes even smaller and more personal. There’s no room in her van – or her heart – for such things anymore.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF NOMADIC LIFE AT MACRO SCALE

There’s another architectural scale at work in the film. This scale zooms out beyond the scale of house, building, and even town; it is the scale of the geography itself. In one scene, Fern is telling someone about her life in her old Nevada home. She first says that it was ‘nothing special’, but she reconsiders and says that it was indeed special. It was a house on the edge of the company-owned town, whose backyard looked out into the open desert and the mountains beyond. Later in the film, we get to see that view when Fern revisits her now-abandoned town for one seemingly last time. She stands at her back doorstep and sees the receding layered landscape of backyard, desert, and mountains far away.

Indeed, the vista of desert and mountains is another ‘room’ of her house. You get the sense that the predilection for being a nomad was always there in Fern’s heart because even in a settled life, she had an affinity for the landscape as part of her everyday vista. In architecture, we are always trying to take advantage of this extended territory of the home. It starts with windows, then balconies, then patios and backyards, and continues with cottages in the woods, cabins on the lake. Seaside resorts and mountain villas. We are always trying to expand our domestic space to try an encompass the natural landscape as part of our home, blurring the edges and boundaries of fences and walls. Even in urban settings, apartments are valued if they have views of the entire city, or if their walls are perforations that connect them sensorily to the surrounding neighborhoods. When I grew up in our apartment in New York the common areas of our housing complex were shared ‘rooms’, extensions of our own apartments, where we otherwise didn’t have room to play or socialise.

For nomads, this is taken to the extreme. The vehicle is meant for the necessities of sleep and privacy, and to store limited possessions, but the real ‘home’ is the entire landscape in which the vehicle is parked. The territorial boundaries are complete blown away, so that when nomads detach themselves from the built environment, they are actually re-attaching themselves to the natural environment. Swankie tells Fern that while she may have given up a lot by becoming a nomad, she has also seen things that she never would have seen if she’d remained attached to a permanent home. Moose, bison, and birds all figure prominently as co-inhabitants of the macro home that nomads now occupy, as do trees and waves and even random people. By minimizing the micro home to its barest essentials, the nomads are able to appreciate the greater architectural scale of the landscape-as-backyard.

I found it interesting and amusing that in Fern’s old house, there was actually a short chainlink fence that separated her actual backyard from her virtual one. It was simply a weak marker of a territorial boundary that didn’t actually exist in any metaphysical way. What is the fence for? It’s not high enough or secure enough for security, so it functions only as a symbolic definition of the legal boundary of Fern’s home. Inside the fence is her physical house, but her metaphysical house ignores the fence completely. She didn’t even own the house outright (the gypsum company owned it), but she owns the world encompassed in that view. And now she actually lives in that macro world rather than her actual house; she never had to buy it, rent it, or take out a mortgage on it.

THE ECONOMIC DIMENSION

There’s scene in the film where Fern gets into a minor argument at a barbecue with her brother-in-law’s colleagues who are all in the real estate business. It’s a quick scene with just a few lines. A lesser movie would’ve made this into a full-blown dramatic conflict, but it blows over quickly and the argument is resolved diplomatically by Fern’s sister. In the scene, Fern complains to the realtors about the economy of home ownership that is driven, according to her, by forcing regular people to go into debt for the rest of their lives for the false security and ‘investment’ opportunity of owning a home. The implication (in context) is that chasing the American Dream is a scam that negatively impacts common working people more severely than others.

While the scene is very short, the theme is actually central to the entire movie. The fact that this is the only time in the film where it comes to the surface is a testament to how skillfully and subtly they make this point elsewhere in the story. The film is set in 2011 when the aftereffects of the Great Recession are still being keenly felt. The recession was fueled by a housing crisis that happened precisely because of the factors that Fern describes. So it’s natural to think that a significant number of people at that time would be turned off by the idea of owning a home and being forced into a kind of indentured servitude of debt for decades, driven by the elusive promise of upward social mobility.

The impact of the Great Recession was such that for the first time in recent US history, parts of the American Dream was called into question. For the first time, there was no guarantee that you’d be able to sell a house for more than what it was bought for. The concept of owning a home had so strongly been a part of the core American mindset that people who who were still renting would be ridiculed if they could otherwise afford to buy a house. They would be told that they were ‘throwing their money away’. But people stopped saying that in 2008.

The film gently proposes that when one attaches oneself too firmly to a THING (house) or a PLACE (town) or a PERSON (family), then one loses a sense of their freedom and their connection to the world at large. One loses a sense of their place in the larger world.

This point is felt keenly through the architecture of the film. The impossibly beautiful landscapes with their impossibly beautiful sunsets, viewed by simple people sitting in cheap lawn chairs, sitting next to their simple camper vans… this is held in stark contrast to the industrialized architecture of a buzzing, automated Amazon warehouse, which is itself a stark contrast to the dusty, abandoned US Gypsum factory where Fern and her husband worked. We see both the past and future of industrialised economies. Even the elegant farmhouse belonging to Dave’s family is seen as an idyllic, almost-artificial representation of a typical TV house, and Fern doesn’t buy the illusion. In fact, she’s frightened by it.

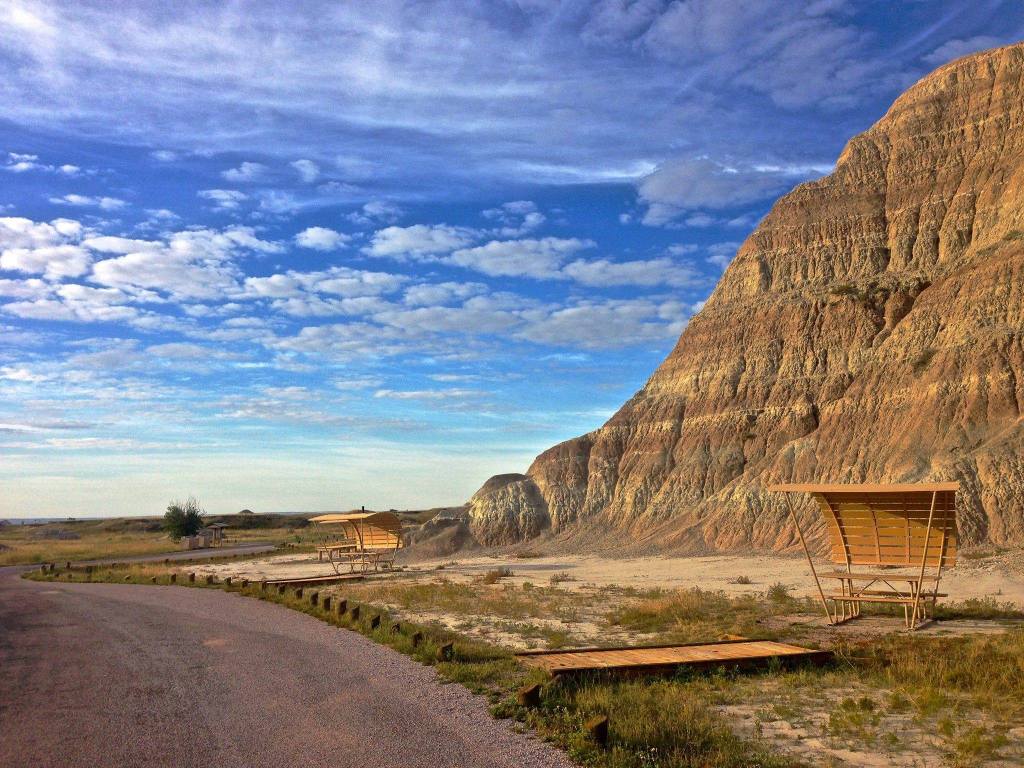

The simple camper vans used by nomads – even though they are machines themselves – represent an organic architecture that fits better in the wide open landscapes of South Dakota and Nevada. The vehicles are almost all white in colour and not ostentatious; nothing like the massive, glitzy luxury RVs we see in the earlier scene. They don’t take up much visual space in the natural panoramas of the desert, and the nomads make it a point to leave their campsites without a physical trace of their time spent there (“pack in, pack out”). Even the architecture of the National Park Service facilities in the Badlands is minimal and organic.

Traditional capitalistic objectives and processes are rejected by the nomads, and the architecture reflects this. When they have to, they rely on the facilities afforded by an industrialised society. Fern earns most of her yearly income from her seasonal Christmastime Amazon job and at other seasonal tourist-driven locations. She has to park overnight in gas stations and rest areas. And when she needs money to repair her van/home, she’s forced to borrow it from her sister living in the suburbs. Adding insult to injury, she has to pick up the cash in person. But these are occasional sacrifices and acknowledgements that enable nomads to spend the rest of their time off the capitalist grid. They don’t worship at that altar; they simply bow to it in passing. They have detached themselves from the rigid architectural framework of the American economy and focus instead on the loose architectural topography of the American landscape.

In Nomadland (the culture as well as the film), architecture is pared down to its minimal state. it exists in just the vehicle and its accessory accoutrements. The balance between built and natural environments is skewed heavily to the latter. HOME is no longer the same as HOUSE or PROPERTY; it is a PHENOMENON. A front porch is not just a structure, but a vista. A backyard is not only a fenced-in perimeter, it’s the entire desert. Architecture is no longer confined to rooms, or walls, or gardens or even to anything bought or sold. It is the world itself, and it’s only through detachment that one comes to realise it.

DETACHMENT FOR ME

What implications does this film and its themes have on me, as an architect and homeowner? During the Great Recession of 2008-9, we never owned a house in the United States. We were always renters. There was a brief time immediately before the market broke that we thought about buying a house, but I was suspicious of how easy it was to get a loan with practically no down-payment. I’ve struggled a lot with credit in my younger life, so it was odd to see mortgage companies practically begging to lend me money. I was skeptical and I’m glad that I was, because in 2009 when we decided to move to India, it would have been infinitely more difficult to do so if we’d had to sell a recently purchased house at that time. We would’ve lost a lot of money.

We had already bought our apartment in India, paying in cash before construction, so when we moved here it was much easier for us. We were lucky to have avoided the Great Recession relatively unscathed, and I will always have my skepticism of the great myth of home ownership to thank for it. I’m not a nomad, although sometimes I do think about just dropping everything and living for a year or so in a van. I get restless sometimes and the urge to travel is always there. I guess it’s good to be in a sort of in-between life where one has the security and stability of a permanent home, but one can remain detached enough from it to understand the worth of leaving it occasionally to take stock of the world outside. The global pandemic has obviously hindered this, and we are now all ‘attached’ to some sort of dwelling place in numerous frustrating ways. But hopefully it will end soon enough to wander again and to appreciate what the natural world has to offer.

If anything, Nomadland made me think about whether I could hypothetically leave everything behind and just wander the land with just a few possessions. As an introvert, I don’t mind being alone, but I don’t think I can detach myself in that way, nor do I want to. I also think that detachment doesn’t always have to be physical; it can be mental and spiritual, and in some ways being able to live in a place (or be in a situation) yet still be detached from it can give you a deeper perspective as well as a sense of freedom. At the very least, it can make you appreciate what you do have, and not take it for granted. And when I think about architecture going forward, I’ll try to think more about envisioning architecture that is not itself so detached from the world and landscape around it. Architecture that is subtle rather than grandiose, and permeable rather than opaque, and perhaps attached to the right things.