FIXING THE INDUSTRY-ACADEMIA MISMATCH

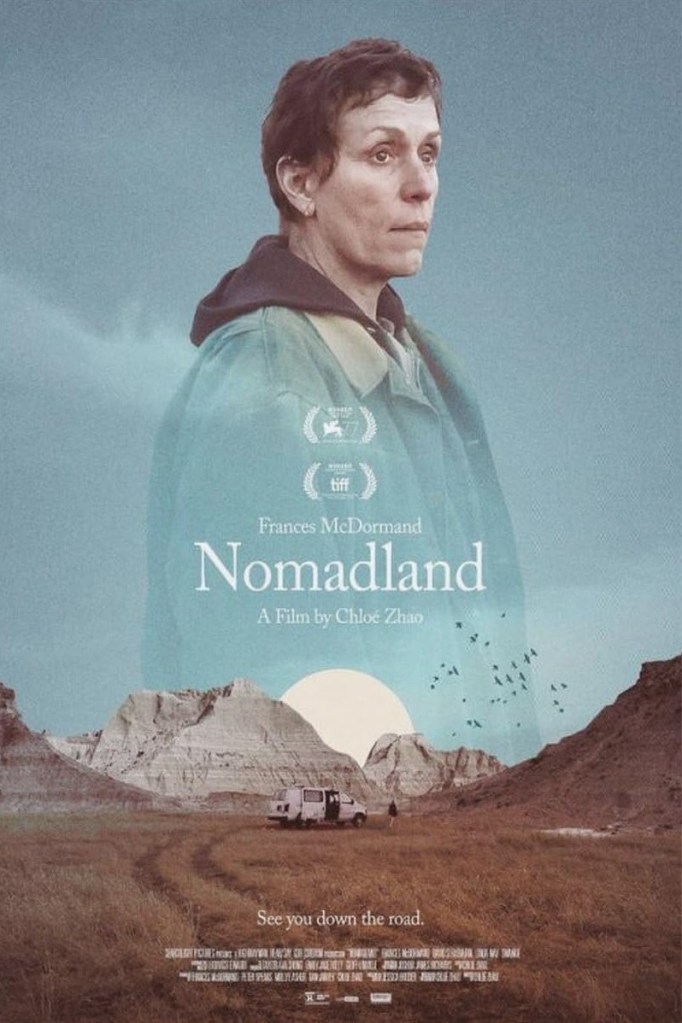

A few years ago, at a design event in Delhi, I met a talented and well-known architect who had hired a few of my interior design graduates in the past. In fact, a former student was working with him at the time, so I naturally asked him how she was getting on. He acknowledged that she didn’t come in with a huge bank of knowledge (especially being an interior designer working for an architect), but he was fine with that; he liked that she was thoughtful, hardworking, eager to learn, and never turned down an opportunity to work on tasks that were beyond her initial skillset. It was her attitude that impressed him, more so than her skills or knowledge.

I was really happy to hear this. It was a validation of everything I try to do as an educator. I know full well that there’s a lot of pressure on academics to prepare students to meet industry expectations even though no one can really agree on what that actually means. Instead, I try to focus on making my students adaptable, confident, courageous, and willing to learn. That will help them far more than grooming them for any particular industry. I left that meeting thinking that it’s better to groom my students for such employers rather than what some vague and nameless industry is actually looking for.

Above everything, it’s not even really fair to use the word industry when we’re talking about design and architecture. My friend and long-time colleague Tapan Chakravarty prefers to use the word profession instead and I agree with him. Designers are professionals after all, and while there’s nothing wrong with industrial labour, we’re not grooming designers to be factory workers. On the other hand, most of what I want to write today is not just about the design profession, but all the related disciplines associated with it – builders, contractors, labourers, vendors, artisans, engineers, brokers, and so on – all of whom collaborate with designers in some way. The only easy way to classify them all is the word industry so with apologies to Tapan, I’ll keep using that word for now.

Academia and Industry – An Unbalanced Relationship

As a full-time academic, when I have conversations about the relationship between industry and higher education, I admit I tend to get somewhat defensive. That’s because it always seems to boil down to a one-way relationship, focusing on what industry expects of us and how we’re meant to churn out employable graduates to be gobbled up by the work force. It always seems to be about what we can do to serve industry, and not enough conversation about what industry can likewise do for academia, except to act as jury members and examiners, and occasionally as advisory board members. Even these functions tend to place academics in a bit of subordinate role to industry, as if we’re desperate for their acceptance and approval. This shouldn’t be the case. The relationship between academia and industry should be more balanced and equitable, and it should be mutually beneficial with neither as subordinate to the other.

I sometimes get the impression that industry’s expectation of graduate readiness assumes that colleges are simply vendors who provide a necessary product or service for the industry to use or consume. I jokingly worry that if my graduates don’t meet a certain standard, employers will ask me for a refund. Of course, no one ever does, but I have read many articles and listened to many employers complain about colleges not providing them with graduates who have the necessary skills and competencies to do the work expected of them. I find this dynamic interesting because in academia, there’s an ongoing debate about having to treat students as “customers” to whom we’re beholden to provide a certain standard of service. Are we similarly beholden to industry? Is industry just another customer who is always right?

And why is there such a strong focus on industry readiness? Colleges themselves fall into this mindset, literally promoting their educational brand as making students industry ready. But what is industry readiness? Is that even possible? There’s no monolithic and singular industry which has a standard set of requirements. The design industry itself is famously varied in terms of employment scenarios. A design graduate is as likely to work for a two-person boutique firm as a giant multinational corporation. How can higher education make students ready for industry that has such a wide and diverse playing field? Not to mention that many design and architecture graduates end up working in different disciplines altogether, and there’s nothing wrong with that. So preparing students to meet a wide variety of industry expectations with just one standard curriculum is exceedingly difficult.

Another problem we face is funding related. Universities used to be hotbeds for innovation (and still are, in some few cases). Most of the ground-breaking research and innovation in a given field used to happen on a university campus because it was the place where one was free to experiment without ordinary constraints of time and profitability. Industry (and other stakeholders like government) used to fund innovation on university campuses extensively. Nowadays, with a strong focus on start-ups and in-house innovation cells, most of the real innovation is happening in the corporate or VC sector. And in any case, such financial support rarely ever reached design schools in any real way. Universities and design schools have become employment factories instead, because this is what both students and industry seem to want. A four-year design programme has become a venue for learning a set of basic technical and software skills, along with grooming for corporate recruitment and training.

On the one hand, academics are urged to be funding-agnostic, because education shouldn’t be transactional, even though it often appears that way. We have pressures to be egalitarian and provide equal opportunities to underprivileged students via scholarships and fee waivers. But with no other sources of revenue in the traditional private education model, how can we simultaneously reduce fees and also spend money to cultivate cutting-edge innovation? I remember my time as a Dean, having to balance a budget between paying high salaries to attract good teachers and providing adequate workshop infrastructure (adequate, mind you, not even cutting edge) while simultaneously ensuring that all students were treated fairly and given equal opportunities to learn by keeping fees reasonably low. Industry doesn’t have such a burden to be egalitarian; they hire whomever they want and pay whatever the market can bear. Of course, industry does have to face the ups and downs of economic cycles, but then again so do private colleges. There are lean years in educational enrolments as well, yet we’re still required to provide the same quality education regardless. So where’s the room for innovation in this tight financial model, without other sources of funding? Where’s the angel investor for academia, especially in a country like India that has no culture of alumni fundraising?

Finally, there’s a proprietary problem. Even if colleges manage to secure investment or participation from a certain industry player, we’re bound to align with only that company because of competition clauses. If we collaborate with Pepsi, there will surely be a no-competition clause that prevents us from taking up a similar project with Coca-Cola, should the opportunity arise. If we get HP to set up a computer lab and promote it, we wouldn’t be allowed to do a similar promotion with Dell or Apple. This kind of exclusivity could potentially become more constraining than having no support at all.

What Industry Should Do

In general, I think industry could do more. I think industry needs to look at academic collaboration as an investment. If they can integrate more into academics across the board, they can reap a richer benefit than simple industry readiness which is actually a meaningless term. In particular, design has historically been an apprenticeship discipline. But now, employers expect graduates to be readymade designers or architects from the get-go. Design education will always be incomplete in that regard, and employers need to stop holding graduates up to an impossible standard. I once had an architect recruiter complain that my student didn’t know how to select proper door hardware, and I couldn’t help but wonder what kind of employee was this person actually looking to hire? When I graduated, I barely knew anything about doors, let alone door hardware. That’s what job experience is for. If, as a teacher, I have to spend my precious class time focusing on information that’s anyway likely to be obsolete by the time my students graduate, then when will I teach them what I actually think they should learn – conceptual thinking, observation, research skills, ability to reflect, eagerness to learn?

I think lately too many employers in design and architecture have absolved themselves of the responsibility to supplement a graduate’s academic knowledge with professional knowledge. They are expecting readymade, industry-ready graduates when such a thing is actually impossible to create, because there’s no single industry profile for which they can be made ready. Employers instead should fill in those gaps, and they should accept that graduates should be taught more for eagerness to learn than for knowing all the skills necessary to sit at a desk in a design studio and start working on projects from day one.

The industry should also be more open to collaborations with academia, more than what they currently do. They should initiate projects (like competitions) that have more flexible timelines and criteria so that students can plug into them within the constraints of their academic calendar. Certain company staff can be given dedicated roles as academic liaisons (not just as recruiters and trainers), so that such collaborations can be more meaningful and integrated. Companies should also be more willing to go beyond collaborating with only the ‘top’ design schools, which actually make up only about a very tiny percentage of the aggregate pool of design graduates.

What Academia Should Do

But the burden isn’t only on industry. Academia can also do more. The first step is to relinquish the subservient mindset and put themselves on equal footing with industry. Professional guests and collaborators should be treated as equal partners, not VIPs or royalty. The second step is to break the ‘blame chain’ and avoid turning about and complaining that schools are the problem. Too often, I’ve heard my academic colleagues complain that schooling has done a poor job of preparing students for college. This may in fact be true, but it doesn’t help to sit on the sidelines and complain. If we expect industry to collaborate better with higher education, then higher education needs to likewise offer to collaborate with K-12 schools, and not just as feeders for admissions. I remember getting excited a few years ago when one of my colleagues initiated a program to train school teachers to teach design thinking. Unfortunately, that project didn’t fully take off.

Another step is to allocate dedicated faculty to act as liaisons with industry, mirroring the same staff members on the industry side. These academic liaisons should be faculty themselves, not corporate staff, so that there can be smoother integration with the curriculum, which only the faculty know well. Of course, these faculty should be given the bandwidth (and authority) to do this work, not on top of their existing teaching loads. Every teacher doesn’t have the ability or even the ambition to become a Department Head or Dean. So such alternative roles can provide additional pathways to professional growth. I have yet to see a design school in India (to my knowledge) with someone in the position of ‘Associate Dean for Industry Outreach’; this should be a role in every design school from inception.

Academies also need to restructure their curricula to allow industry to fill in the gaps where they potentially have more expertise and opportunity, in subject areas like technology, leadership, management, or entrepreneurship. Colleges too often try to offer everything in one package but this isn’t possible, especially for smaller design schools that don’t have diverse faculty resources. Curricula should be designed to be flexible in these subject areas and allow students to learn the competencies in ways other than the traditional classroom setting, and no, the typical internship or training period is not the only answer. Live projects, consultancies, and other opportunities should be given a higher priority than they currently have in a design curriculum.

Finally, incubation needs to be given proper resources and attention. It can’t be just a co-working space in the corner of a college campus. Colleges with good incubation cells have fully integrated them not just into their campus space, but into the curricula as well. I once visited some former students who had set up their own practice a year or so after graduation. They were set up in office space not 5 minutes’ drive from their former campus. I asked why they didn’t take advantage of the newly set-up incubation space on campus itself. Their answer was that they were anyway using space in the factory owned by one of their parents, so they were able to use the space rent-free. Plenty of other start-ups similarly begin in private homes, in basements, attics, and garages. My students didn’t see a value in the college incubation cell because they only saw it as discounted office space, which they didn’t need. But incubation has to be seen as much more than that. My students ideally should’ve been aware that, in being part of the incubation cell, they would have access to shared infrastructure, resources, and faculty mentorship, as well as a pool of in-house student talent to help them with their projects. As alumni, they could have been industry mentors for their junior classmates while providing valuable opportunities for live projects built into the students’ curriculum, all of it outside the traditional internship model. In my opinion, this was a lost opportunity.

What Students Should Do

Of course, students themselves need to see the value of meaningful industry collaboration. Many students, especially in India, are so dead set on getting a lucrative job after graduation that they tend to miss the most of what college is teaching them. Students seem to want to learn the skills to land that first job, exclusive of almost anything else. Their mindset also needs to look beyond the ‘job’ as the only way to fulfil career aspirations. A job is all well and good, but there are so many other career experiences one can follow to achieve professional growth. Design students should be made to see the career value in research, writing, business, entrepreneurship, and other aspects of life that are tangential but related to their chosen design discipline. Getting hung up on learning X or Y software suite can be a waste of energy and attention in college. The deeper learning is about independence, decision-making, communication, articulation, reflection, observation, time management, task management, and myriad other parameters that are what the design industry is actually looking for, beyond simply X or Y software proficiency. Design education (like the profession) is more than just an aggregate of skills, and if industry needs to accept this, then likewise so do students and faculty.

This article may come across as being overly defensive, but I’ve also tried to offer solutions to the problem of industry-academic mismatch. Both sides of this problem need to see each other less as vendors or customers and more as partners and collaborators. Indeed, this is what many academicians and professionals say they want to do, but there are things they can initiate that can make this easier. Mindset change is the beginning of it, followed by real (not superficial) integration and cooperation. Either side can’t just add collaborate to business-as-usual; the fundamental model must significantly change.