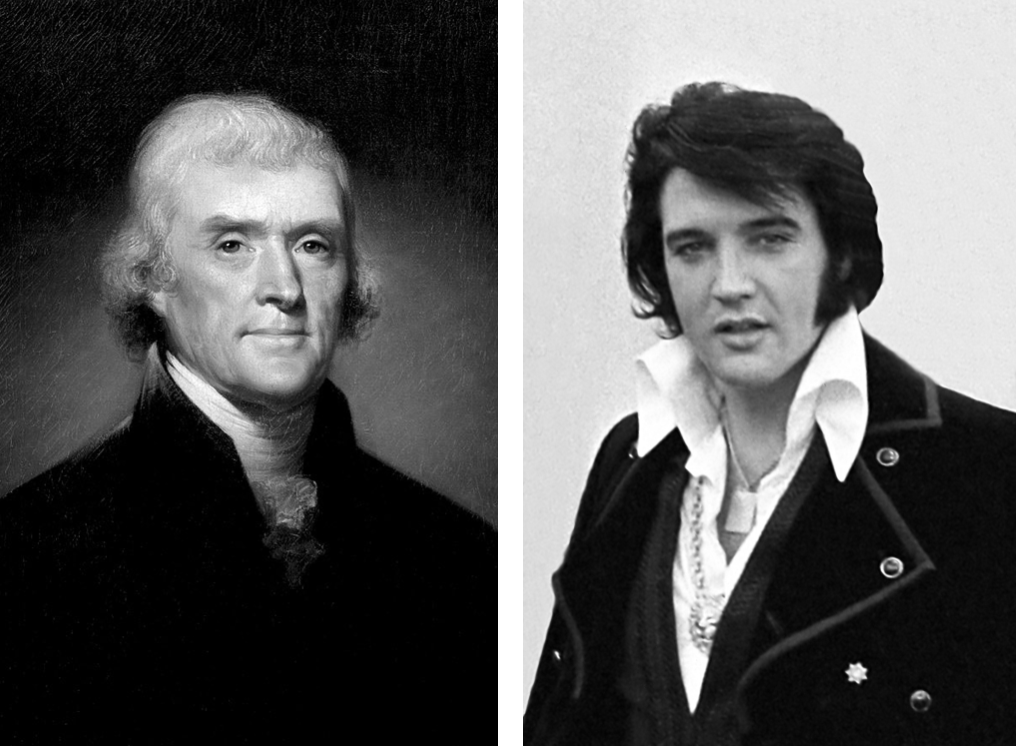

When was the last time you thought of Thomas Jefferson and Elvis Presley in the same context?

Elvis Presley portrait by Ollie Atkins, 1970

Last week I brought up these two personalities in a class discussion about aristocracy, and that was likely a first for me. This semester, I’m teaching a class on the Evolution of Spaces in History in which last week’s topic was Aristocratic Spaces – an overview of historical forts and palaces of India. Every week, I ask students to give a lecture on the week’s topic, which is followed by a discussion and then a debate prompted by a provocative statement.

This week’s provocation said that the government, as the nominal owner of these forts and palaces, should sell them to modern-day celebrities, who would take up the architectural legacy of these places and live there in splendour like the modern-day aristocrats they are – corporate leaders, movie stars, musicians, athletes. These are the people that have replaced the rajahs and emperors as the aristocrats of modern society, so doesn’t it make sense that they should occupy the spaces historically reserved for them?

The provocation was a hypothetical statement meant to stimulate a discussion about the changing nature of aristocracy in the social order. It generated a lively debate, but it got me thinking about an American road trip I took in my college days, a road trip that illustrated the near-perfect alignment between the aristocrats of the past and the present. And this is where Jefferson and Presley came into the picture.

The Road Trip

During spring break in 1996, my friend Larry and I decided to take a road trip from New Jersey down to New Orleans. Neither of us had ever been there, and my cousin was studying architecture at Tulane University, so we thought it would be a good opportunity to see the city as well as visit another architecture school. The drive takes a couple of days so along the way we visited two places we’d always wanted to see – two sites that figured prominently in our architectural and cultural heritage.

The first was Monticello, the Virginia home of Thomas Jefferson – statesman, architect, third President, author of the Declaration of Independence, and founding father of the American nation.

The second was Graceland, the Memphis home of Elvis Presley – singer, actor, prolific hip-shaker, author of Heartbreak Hotel, and founding father of American rock-n-roll.

It was well after our road trip had ended when I reflected on the bizarre similarity in visiting these two holy shrines to American culture, one after the other. Sure, there are differences between them. One is highbrow; the other is decidedly lowbrow. One is centuries old; the other, decades. One was owned by a politician and bureaucrat; the other by a popular entertainer (a distinction that has recently blurred, I know). One is situated on a quiet, pastoral, country estate; the other in a metro city on a main traffic artery. But as I now think about the physical visits to both of these places – the similar sequences, narratives, highlights, and commentaries on the lives of the men who lived there – I can’t help but dwell on how celebrity and aristocracy are perceived by the masses. How we perceive the lives of people who have shaped our collective culture. Who we admire and look up to over time and what that says about our own evolution as a society.

The Home of an Aristocrat

There is so much that was comparable in the experience of visiting these two monuments (or at least twenty-five years ago when I visited them). When you reach Monticello, you park at a visitors’ center, purchase a ticket, and board a minibus that takes you up the estate itself. Same with Graceland, where you board the bus for a short drive across the street up the similar long, circular driveway leading to the house itself. Both are situated at the crown of a hill, overlooking a wooded and grassy estate.

The houses are both stately mansions with a similar classical façade – symmetrical, with a central entry portico with standard neoclassical elements of columns and pediments. Both are meant to evoke the psychological image of “home” while sending the clear signal that someone of importance lives here.

When you enter each home, your tour group of about 10 tourists is taken through the various rooms of the houses, while the tour guide offers a descriptive commentary on the life of the prominent man who lived there. I don’t think there could be two men more different than Thomas Jefferson and Elvis Presley, and indeed the décor of both places bears this out. You won’t find mirrored ceilings or crushed velvet cushions in Monticello, and you won’t find ancient oak floorboards in Graceland. Both homes look exactly how you would expect the homes of their residents to be. Jefferson’s home is dignified yet rustic while Presley’s is kitschy and opulent. Both are designed with innovations that reflect the lifestyle of the owner – Jefferson built his modest bed into the poché and installed a dumbwaiter from the wine cellar hidden in the dining room fireplace. Elvis outfitted his basement with a wall of television screens and stereo equipment.

Only one of the tour guides mentioned the owner’s predilection for fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches. I’ll let you guess which one it was.

Both tours culminate in a visit to an onsite museum of the owner’s personal memorabilia and both end with a short walk to their respective grave sites, where visitors are expected to pay their final respects to two men who profoundly shaped the culture of their country, but in two markedly different ways and in two very different eras of American history.

Aristocracy Evolves

What does this say about aristocracy in America, or anywhere for that matter? What does this say about who our society values, past and present? Both Jefferson and Presley are deeply revered and memorialized. Both served their countries as patriots through critical wars – Jefferson as a politician, and Presley as a soldier. Both were populists, admired and well-liked by the common man. Are both aristocrats?

Jefferson fits the description in the traditional way. He was literally a member of the landed gentry and was as close to a feudal lord as one would find in democratic, colonial America. But such people are few and far-between in modern society. Powerful men these days are not known to be gentleman farmers. Numerous late night talk show hosts have made light of the fact that a photo of a pop star is more recognizable to the modern general public than a historically important politician or wartime hero. People model their lives and lifestyles on the personalities and behaviours of entertainers, not on the philosophies of founding fathers. And most would admit that real political control lies more in the hands of corporate oligarchs than in the people who are actually elected into office.

Yet the admiration we have for them is the same. The influence they’ve had on our lives is the same. The affluent elite of today garner the same level of attention and admiration as the landed aristocrats of yesterday (as well as the same reproach and infamy when things go wrong). The lords and landowners, princes and emperors are no different in that respect than the powerful influencers of the modern world; they hold the same sway over the way we live and they wield the same level of power to impact our lives.

The reasons for this are too many to discuss here, but I think a lot of it has to do with the emergence of democracy as the new paradigm for global governance. People’s heroes and influencers are nowadays more likely to have emerged from humble beginnings rather than from inherited nobility. Information technology has likewise made it easier to disseminate cultural mores; every day a new hero or celebrity is born and every day an old one fades away, and we get to know of it instantly.

During the students’ presentation on Indian forts and palaces – spaces of historical aristocracy – I hoped that they would end the talk with a picture of Antilia, the bombastic home of India’s wealthiest industrialist, Mukesh Ambani. To me, Antilia is no different from Amer Fort or Mysore Palace, and represents the culmination of that architectural evolution of aristocratic spaces. Each represents the glory of a powerful family, each in its own ostentatious yet magnificent way. Each represents the fantastical ambition and aspiration of the common man whose life is impacted by the aristocracies that rule over him.