My third year architecture students are supposed to start their internships at the end of this semester, and the pandemic has got them a little worried about their prospects. Last year around April and May, their seniors were stuck in a difficult situation – the lockdown here in India was in full force, and they all had to either find internships that they could do remotely or find internships in their hometowns which, for the large majority of them is here in Agra – a Tier II city in India that… erm… how do I put this… isn’t very high on the aspirational lists of places to do an architecture internship. Since the Covid pandemic had taken a major economic toll on many architecture firms who suddenly couldn’t do any work, and considering we were even wondering whether they would get internships at all, they were fortunate enough to all find positions somewhere. Now, the current batch of students is justifiably wondering whether they’ll be in the same situation in the next few months.

In such uncertain times, it’s hard to predict even a few months into the future, but I think things will be better by then, and they’ll be able to find work in other cities. The industry was hard hit by the pandemic and I don’t think it’s recovered fully yet, but things are better than they were nine months ago.

I spoke to them last week at length about preparing their portfolios, and near the end of our discussion we started talking about getting paid for internships. Yes… we opened that can of worms.

Now, before I say anything about this… this has been an oft-discussed, hot-button topic for a long time in the architecture profession (and in other design professions). There doesn’t seem to be much to add to the conversation, so I’m not entirely sure why I’m even writing this. Maybe just to put my own opinion on the record. Maybe because, despite all the debate and dialogue, we’re still nowhere near approaching any significant movement in the problem of unpaid internships in architecture.

While contemplating this topic as a blog post, I thought about starting with quotes from a few articles or opinion pieces on this topic, but… there are too many. It’s kind of like being a waiter at an all-you-can-eat buffet. You don’t need me to google that for you. Suffice to say, it’s an ugly aspect of our profession that somehow doesn’t want to go away.

In any case, my position on unpaid internships is that I’m thoroughly against it, both as a practitioner and an academic. I’ve hired interns of my own (and paid them), and I’ve sent my students out into the wild to become interns, and neither of my personas thinks it’s fair to not pay young people who perform work in your office that you’re getting paid for. If you’re not getting paid enough to pay your interns, then you have no business hiring them. Or you can take it out of your own income. I teach professional ethics in the classroom, and this is one of the clearest breaches of ethical practice that is somehow still commonplace in our profession.

That’s a rather ruthless way of putting it, I know. I have friends who run architecture practices that don’t pay interns. How can I continue to accept their behaviour in good conscience? How do I reconcile their otherwise good work with this arguably bad practice? The truth is that my position on unpaid internships is idealistically and unwaveringly clear, but I do retain some empathy for why it exists. I know that there are underlying problems in the entire profession itself that make unpaid internships a ‘necessary’ evil, and these problems don’t seem to be going away.

The central issue, of course, is that architects themselves aren’t paid enough. Given the length of their education and training, the breadth of their responsibilities, and the gravity of their legal liability in construction projects, architects are paid nowhere near what they deserve. Running an architecture practice is like riding a constant knife-edge between profitability and ruin, and the only reason we continue to flog ourselves through it is because of how stubborn we were taught to be in architecture school. That initial first year reading of The Fountainhead, as misguided as it ultimately turns out to be, makes it too hard to disassociate our internal Howard Roarks from our external selves. We’re going to make architecture, by God, even if we die trying!

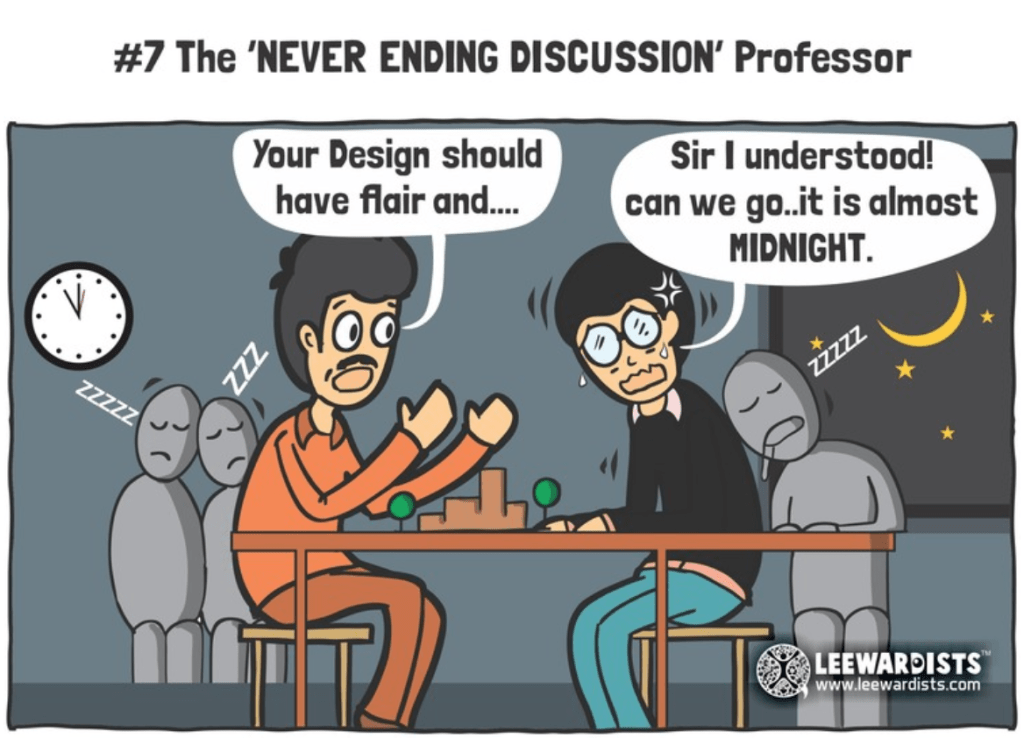

But I’ll address the problem of finances in a minute. There are several other reasons people give in defence of unpaid internships, and the most common is that interns are apparently a net liability in a given architecture practice. The claim is that it costs more time, resources, and money to teach interns about the profession than the benefit derived from them. Interns (usually in their fourth year of education, here in India) are generally considered not much more than newborns in the life cycle of design maturity. They know some CAD, Sketchup, and Photoshop, and how to file away things, and perhaps know the basics of construction and materials. Interns are rarely asked to design anything, nor are they asked to manage construction. The reasoning is that the complex nuances of how to deal with labour on a job site require at least a few years of seasoning. Many architects tell me that they really don’t have the time to teach their interns anything, and the work that they do can be done by technicians and draftspersons who are already on staff and require much less oversight. In fact, some interns have told me stories about architects who, instead of paying them, demand to be paid a fee for taking on an intern. I’ve only heard about such incidents anecdotally; I can’t imagine any of my friends or colleagues being that pretentious and arrogant.

My rebuttal to this defence is that, for millennia, architecture has been a profession founded on the principle of apprenticeship. It’s only been a century or so that architects actually go to college for an architecture degree; most architecture education was on-the-job training. This is still generally true – most experienced architects will agree that the majority of what is to be learnt in architecture comes after graduation. The five-year course is just teeing up the ball for the real training-in-practice; it’s a foundation that primes you to be in a position to learn further. Given this long tradition of apprenticeship, I find it unconvincing when architects expect fresh graduates to be fully groomed for the profession. Do they think that they’re absolved completely from being part of the education of their employees? Interns are simply apprentices. They are there to learn to become architects. There’s a well-acknowledged limit to what we as educators can do to prepare them for work. College may be a safe space for students to explore and stretch themselves in their investigation of design but it can’t also provide the entirety of their practical and rational knowledge. Every architect in practice has been an intern in some way, and learned something from a working mentor in some way. This is the tradition we carry on as one of the oldest professions in the world, and we should carry it with pride. An architect who doesn’t consider it their generational responsibility to pass on what they know to intern apprentices is not worthy of holding the license they took pains to receive. They aren’t a net liability if an architect factors in their own internship, followed by hiring interns themselves… as a generational way of paying it forward.

Some practicing architects like to point out to us academics that since we get paid to teach students, then why can’t practitioners also be paid? Are they not teachers, too? This is a tu quoque fallacy of a high order. The equation isn’t anywhere near the same. Educators are paid to teach, but we don’t earn a profit from the students’ work. We’re paid regardless of the students’ performance (well, sort of), and the creative work produced by them isn’t a commodity that earns us a design fee. Practitioners, on the other hand, earn income on the basis of the work produced by the workers in their employ. If an architect receives a fee, part of that fee is assumed to go toward the architect’s overhead expenses, in this case, paying their employees. If, for example, you dine at a restaurant, and you pay a tip to a server, you expect that tip to go to the server, or at least be shared with them. You’d be furious if you tipped a server for good service and then discovered that the restaurant owner pocketed the tip for himself. Try to imagine what a client would think if you had interns working on the drawings for their project and the client learned that you weren’t sharing any of their fee with the people who were actually working on it.

Getting back to this issue of finances… Yes, I understand the low margin of profitability in running a design practice. But should that excuse the questionable ethics of unpaid internships? If you can’t pay people to do the work that earns you profit, then you need to learn how to be a better businessperson and entrepreneur. Few other industries make it a practice to make a buck on the backs of slave labour. Even companies like Amazon and Apple get heat for underpaying their workers, but no one is accusing them of not even paying them. Yet somehow this is common practice in design and architecture. Somehow, despite all our discussions about doing good for people, and designing with social conscience, and making habitats for humanity, we forget these values when it comes to simple entrepreneurial economics.

Part of the reason this practice gets perpetuated is also because interns are so willing to accept it. In countries like India, internships are required for their degree and they will be forced to take an unpaid internship if no other options are available (especially during a global pandemic). I certainly don’t blame them; I’ve done it myself. Not necessarily because there were no options, but because there are architects I really wanted to work for and I didn’t need the money. My classmates and I once worked for one of our favourite professors on a competition and he warned us that he couldn’t pay us (although the parameters for competitions are different because the architect isn’t get paid either; more on that in a minute). Ultimately at the end, he did pay us a token amount (perhaps out of guilt? a job well done?), but we willingly took the work knowing that we would get nothing in return financially. In fact, it would’ve cost us money because we had to pay for daily travel and meals. But we were just eager to work in a real-world office environment for someone we admired.

If it wasn’t for the fact that our professor did end up paying us, I might have looked back at that episode with some regret. In the capitalist world we’re forced to survive in, our worth as a working professional is measured in monetary compensation; there’s no getting past that. In most circumstances, getting paid nothing for our work implies we’re worth nothing, and that shouldn’t be true of interns. So I tell my students now that, while I understand their willingness to work for nothing because they either have no choice, or they’re getting a good experience in return, I urge them to still ask for compensation. At least put it out there for discussion; don’t just accept it out of hand. The more interns who willingly accept it, the more practitioners who will perpetuate it.

I’m not saying there isn’t dignity in working for free when the situation demands it. Throughout the entirety of my career, I’ve done some design work for free – pro bono and charitable work. Or professional courtesy for friends or family. Even as a teacher, I’ve given lectures and workshops for no compensation and I’ve invited people to do the same in my own classes. The difference, however, is that when we take on such work from others, both sides are usually on equal footing. When I invite a friend or colleague to give a guest lecture, they do it as a professional courtesy and they know I would happily do the same in return. We both choose to do it, and we accept the choice. It’s different with interns. They’re not on the same professional footing as their employers. The power dynamic is completely different, and they often take unpaid work because they have little or no choice otherwise. This is what makes it not a professional courtesy. It’s simply unfair.

One advice I give my students is to bring it up in the interview by asking “What would be my expected compensation?” as opposed to asking “Will I be compensated?”. This language at least signals to the employer that getting paid is expected and assumed. Even if they balk at it after that, the subtle message is sent. If the intern chooses to work for free at this point, at least that’s a negotiation from a reasonable baseline.

Of course, a major exception I have in my disfavour of students accepting unpaid internships is when the employers themselves are not getting paid for the work. This can cover pro bono projects, competitions, and working for charitable NGOs. If there’s no income being made on the project, then the student shouldn’t have a problem taking on unpaid work, assuming they can afford to do it. (Although to be honest, in one project in which I was doing the work pro bono, my interns on the project still got paid, simply because my reasons for doing it pro bono were not their reasons, and it would be unfair to treat it that way.)

If a salary (even a low one) for profitable work is still not in the cards, then I advise students to at least ask for a token payment that covers their expenses of daily commuting and workplace meals. I ask the same of any employers I know that are hiring my students. An intern shouldn’t have to pay out of pocket to come work for you every day. Of course, it’s hard to cover accommodation in this way. As I mentioned, many of my students aspire to work in larger cities, away from home, and this requires paying for accommodation which, in cities like Delhi and Mumbai where many good firms are situated, the housing rates are exorbitantly high. Of course, the deeper problem with this is a class issue; students who can afford to pay for accommodation and unpaid internships are the ones who will be more likely to grab such opportunities, skewing the balance inordinately against students of lower income brackets. Other biases like gender and caste also exist. In such cases, I ask students (of all income groups) to do a simple cost-benefit analysis and determine if they’re really getting what they’re paying for in this internship. And I ask them to think of their own self-worth in the larger picture.

What else can be done to solve this problem? I think in India at least, the Council of Architecture (our overall regulatory body) should acknowledge it as an ethical conundrum and take on the burden of resolving it. The Council has established minimum fees for architectural compensation, and they require all licensed architects to practice ethical behaviour. The same should be expected for internships since the Council anyway mandates them in college curricula. To me, this is a no-brainer, and I’m frankly surprised why this isn’t already on the table. Perhaps with new leadership in the COA, it will be.

There are other things being done around the world. Some countries are prohibiting architects from working on high-profile public projects if they make use of unpaid labour. Some governments have started the process of potentially banning unpaid internships outright, across all industries. Many university placement offices who help students find internships now require all recruiters to pay their interns a nominal compensation; no unpaid internships are allowed, and it’s great for a college to be in a position to enforce that. All of these are steps in the right direction. And certainly more needs to be done amongst the various professional guilds in each country, like India’s COA and the AIA in the United States. In almost all countries, the practice of architecture – unlike most other design disciplines – is tightly regulated. Why can’t this be included as well?

Those in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones, right? So what can we academics do to help, besides having a real, honest discussion with our students about the realities of the profession they chose? Personally, I think architecture (and design) curricula teach you almost nothing about how to be a businessperson, despite the fact that a disproportionate number of architects start their own businesses earlier and more often compared to other disciplines. Students are rarely taught how to manage their personal finances and save money, how to invest, how to pitch an idea to investors, how to seek and apply for loans and funding. Few graduates are armed with the knowledge of how to set their fees, how to indemnify themselves in their contracts, how to protect their intellectual property. Most of them are taught only to do architecture, and not how to use their broad design talents to diversify into other fields that can earn them steady incomes. I’m talking about things like: managing projects; building their own work (turnkey/design-build); making images and visualisations, or designing furniture, furnishings, lighting, accessories, or fabrications. One of the architects I used to work for had a 3D printer in the office (back when they weren’t ubiquitous) that was mostly sitting around unused. I had read an article about people charging $300 a piece to make 3D-printed figurines of their friends and family members based on submitted photographs. I told my boss that he should hire someone just to do that and have that 3D printer humming 24 hours a day, churning out cheesy knick-knacks so that it could subsidise our salaries, which we often had to forgo when our clients ‘forgot’ to pay us.

Many architects and interior designers are finding other ways to earn a living besides simply offering architectural services; they have retail shops that sell furnishings and lifestyle accessories. Such a thing used to be frowned upon by my architecture professors, as if it cheapened our lofty and noble profession. I now realise that architects and designers who do this are very, very smart. Why is there such a romantic association in architecture circles of the ‘starving noble architect’? Why aren’t we taught the skills needed to earn a livelihood and follow our passions? It’s high time we teach our students to learn how to balance ideological integrity with earning an honest living. Prepare them to understand their self-worth and be confident about their expectations. There’s a lot that we as academics can do for them, if we open up our curricula and find ways to include this.

Ultimately though, architects – and architecture students – need to raise their voices in their respective guilds, associations, and other public forums to speak about this problem, and start dismantling its silent toleration. More opinions need to be heard and more rational discourse needs to happen across the board. More solutions need to be shared. We have to stop assuming someone else will fix the problem and encourage a grass roots movement to fix this. Raise awareness and speak sincerely about the problem, and take a strong stance.

So in the end, I guess that’s why I’m writing this.