I clearly remember the moment when my personality changed forever.

I was always in introverted kid. An only child for fourteen years, and an awkward immigrant for many more, it’s no mystery why, with my shy and nerdy inclinations, I sought refuge in science fiction and fantasy books. They were my world. Too young to leave me home alone, my parents often took me along to their social engagements, a thousand-page book my only company and a safe haven from overzealous grownups asking condescending questions. I was nowhere near a natural conversationalist, and I shied away from engaging in, let alone starting, any dialogue.

Before you get all sobby and sorry for me (“Awww!”), I should make it clear that I did have friends. I did go out and play (although less often after moving to the suburbs). It’s not like I was a recluse. I was just the kind of kid that would prefer to stay in the background of conversations and listen, and this was a trait that continued mostly through college.

Now let’s fast forward to that moment I mentioned, when things changed. It was the summer of 1996, and I was starting my final year in architecture school. My first year tutor, Prof. Craig Konyk, asked me to be his teaching assistant in our college’s Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), which was a program to offer the opportunity of a quality education to a different type of student. My college, New Jersey Institute of Technology, was (and is) a well-known technical institution with the only accredited undergraduate architecture program in the state. NJIT has a diverse student body drawn from many working class and immigrant communities of Northern New Jersey. EOP accepted students who were just below the threshold for standard admission, but it required a one-month residential summer ‘boot camp’ before they joined the rest of their cohort. The idea was to prepare them for the rigor of college life before they started college itself. Not only was EOP successful in bringing more socioeconomic and cultural diversity to NJIT, it often prepared the students better than the rest of their classmates, and many EOP students ended up being the stars of their class.

Anyway, I was asked to be a Teaching Assistant and all TAs had to take a one-day training session by the EOP management. The training was kind of like an informal team-building and problem-solving session and in one of the first exercises, they put us into groups to solve some kind of hypothetical problem. My group of five or six people — most of us doing this for the first time — started the exercise sitting in a circle and just akwardly staring at each other. No one wanted to be the first one to talk. This, in a nutshell, was exactly how all such interactions in my life had been thus far — waiting for someone else to take the initiative in group discussions.

But this time, something was different. Something in me just snapped awake. I don’t know what triggered it. Perhaps it was the four prior years of having to present my work in architecture reviews. Perhaps it was my emerging self-confidence in being a good design student. But I think the biggest factor may have been that I was now 26 — a full-blown adult — and simply fed up of the awkward immature silence in group discussions where nobody says anything.

So I began a dialogue.

I took it upon myself to be the temporary leader of this misfit group, and started asking people how we’re going to solve this problem. I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was the moment that would change my life forever because it was the moment that started me off on two pathways:

First, I think it was that moment in which I started my teaching career, although I didn’t become an actual teacher until a decade later. It was then that I realized that true learning only happens when you open your voice and communicate with others.

Second, it was the moment where I really started to appreciate the value of dialogue in design. When I say ‘design’, I mean it in the broadest sense — design as a way to solve problems — an act of creativity and innovation. I had of course already been doing this in my prior four years of architecture school, but I didn’t fully realize the importance of dialogue until that moment. I realized that creativity only really starts to happen when you take out that… thing… that is bottled up inside and release it to the world.

Design education is built on a foundation of critique. The ability to properly give and take critique is very crucial to the progressive growth and practice of design. And critique happens best through dialogue.

In later years, I came to learn of the Socratic method, and the dialectic in Buddhist scholarship traditions, as well as the pedagogy of ancient education at places like Nalanda University. All of these traditions (and many others) point to dialogue and debate as a means to develop and inculcate critical thinking. This is well-established as a means of strengthening knowledge by exposing one’s existing knowledge to an array of contradictory or polemical thinking. This typically results in a more balanced stance, and being able to adapt one’s knowledge to external critique.

Design requires critical thinking in order to work. It requires the ability to understand and adapt to external stimuli and changing conditions. A design curriculum in an educational institution should not follow a specific code of rules or formulas; neither should it merely be a checklist of skills. Design requires debate. Designers are constantly tasked with defending their proposals against contrary thoughts and opinions, and almost always have to change their proposals in order to make them work better, or make them more feasible, or innovative.

This is one reason why design education, as compared to other traditional disciplines like science or commerce, is often slow to adapt to an increasingly digital context. This is despite the fact that, in the current world of constant connectivity, communication, and exposure to vast quantities of knowledge and ideas, most design debate still happens in person. To be sure, digital technologies and social media have exponentially increased the opportunity for dialogue between people of different cultures, geographies, languages, and contexts. A typical design student in 2018 has the benefit of truly vast quantities of information that were relatively unavailable to previous generations. And indeed, this has opened up design to extraordinary new avenues of thought and innovation, both simple and complex. Western designers can be inspired by a YouTube video that highlights a simple design solution to illuminate homes of the poor in the Philippines. Meanwhile, the same platform allows a college student in India to listen to a TEDTalk at UCLA on quantum computing.

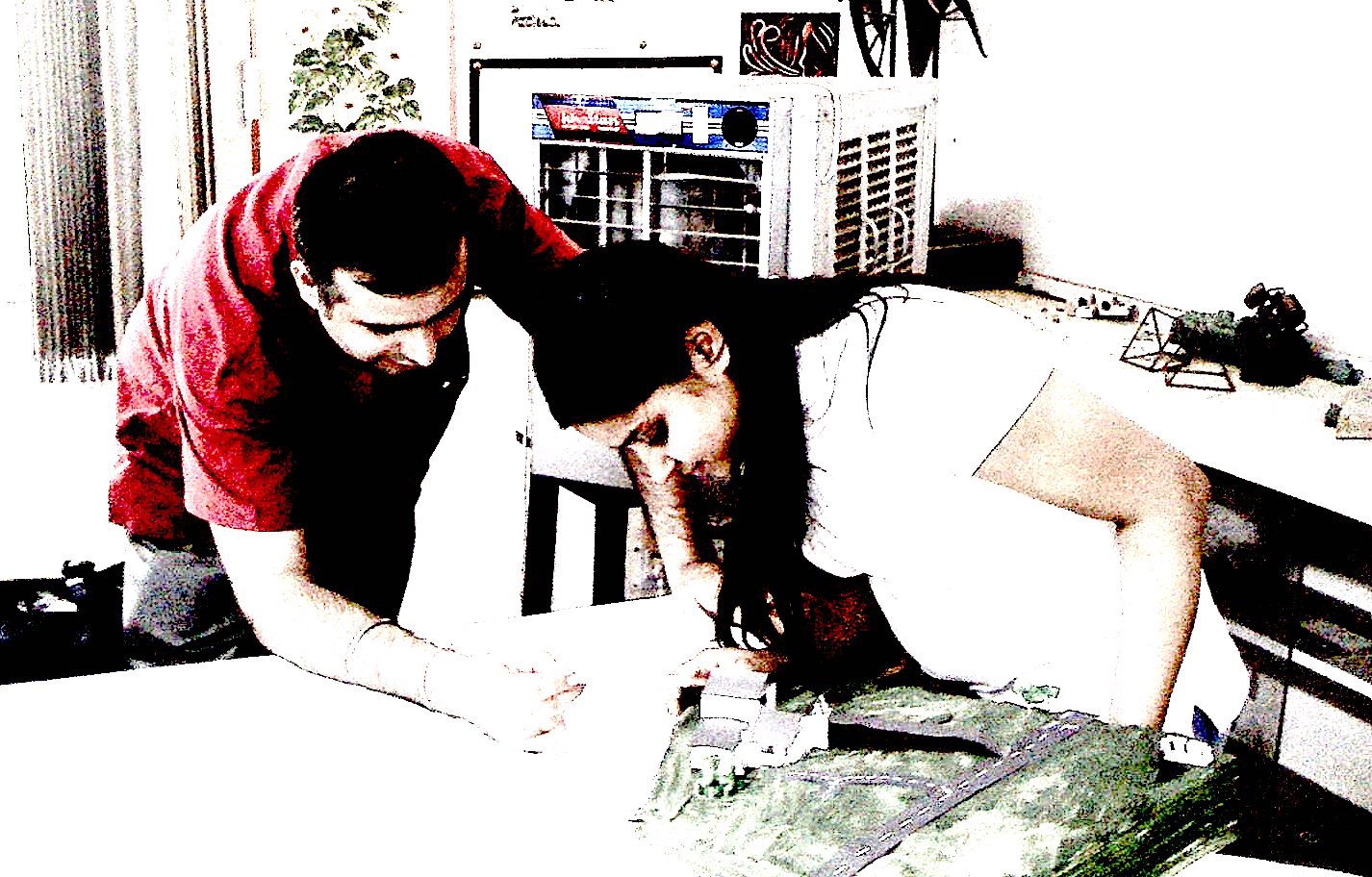

However, at its basic level, learning to become a designer still involves the simple dialogue that happens when two people sit at a table with drawings, sketches, models, prototypes and they simply discuss the problem at hand.

The typical mode of feedback in design — the jury, or review, or pinup, and not an examination – is the primary means of assessing whether a design proposal works or not. Examinations, where a student provides a set answer to a set question and a typically faceless examiner in another room and place assesses whether that answer is correct or not, has little place in design education. In a design jury, a student presents his or her work, and a group of experts give their opinion on it, and usually provides suggestions on how to make it better. The group of experts don’t always agree with each other, and the students themselves don’t always agree with the feedback that is given. That’s all part of the dialogue of design critique, and it reflects how design works in practice as well. A designer is given a brief, works on a proposal, and shares it with the stakeholders (clients or users). They discuss, compromise, and sometimes argue and disagree, and they figure out how to go forward.

The result of this is that the student (and the professional designer) improves his or her design through dialogue, expands his or her knowledge, and goes through an iterative process that strengthens not only the quality of the design but the quality of the designer as well. The designer becomes more confident, more agile, and can better adapt to changing contexts. I might argue that indeed, this is the only way that a designer can become better. Good design requires validation for it to solve the problems it intends to solve, and dialogue can be the vehicle for that validation. Dialogue validates design. Dialogue drives design.

This not only facilitates a better designer, but a better person. A person who engages in dialogue shows that he or she does not have rigid ideas set in stone and is empathetic to the opinions and contexts of others. A person who engages in dialogue is often willing to take feedback, and to compromise and make adjustments to find real solutions. Thus, dialogue needs to be at the heart of any design endeavour, both in practice and in academia. (Fun fact: I believe this to such an extent that I named my own practice ‘DIALOG’.)

Many of my current colleagues and friends hesitate to believe this, but I’m still the same introverted kid that prefers to sit in the background with a book in hand and simply observe what’s happening. The difference is that I’ve learned to use the power of dialogue to try to improve myself and my situation. To try to improve my design. If I’m disconnected to a situation and have no interest in resolving it, then I revert to that inward-focused state. But when there’s a problem that needs to be solved, and I have a vested interest in its resolution (either as an academic or a professional designer), then there is no doubt that I will use what I learned that day in the EOP training session — I will voice my opinion, discuss it with others, and try to find a way to make it work. Sometimes I do it digitally [Thank you, Late-90s’ Internet Discussion Forums for that skill!] and sometimes I simply sit at a table with someone else and initiate a dialogue. Because dialogue drives design, and design solves problems. And there are still a lot of problems out there to solve.

(This article was originally published on Medium on 23 May 2018.)

Pingback: the new abnormal? | PALIMPSEST